Another proxy theatre of war opens

The mainstream commentariat’s assessment of the war between Hamas and Israel is cast in a narrow dimension of a ‘territorial war’.

While it is definitely that, and we are not here to take either side, our view is unequivocally that the wider perspective of this war’s role in the paradigm of the great power contest between USA and China will become increasingly obvious with the passage of time.

The newly opened Middle East theatre of war involving Israel and Hamas in Gaza will likely evolve to include more states such as Syria, Iran, and other regional states fronted by non-state actors such as Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas in Gaza, and Houthi rebels in Yemen. This war is likely to prolong alongside the Russia/Ukraine war.

These two theatres of war, and there could be more that open up in other regions (North Korea?), are designed to engage the US to satisfy a grand strategic objective of China, as discussed in the following passages.

The next two decade’s great power contest – China switches from being timid to assertive

China aims to be second to none as a global superpower. Please take note, as its goal couldn’t be clearer!

Over the past decades, it has acquired the necessary resources and means and seems quite driven. China is fuelled by the ambition to reach the pinnacle of global power, where it believes it rightfully belongs. It anticipates achieving this peak by the year 2050, coinciding with its centenary celebrations as the People’s Republic of China. By that time, China aspires to be the global hegemon, a singular superpower. In terms of the timeline, the anticipated deadline for this goal is only a couple of decades away.

Since the rise to power of President Xi Jinping in 2013, China has pivoted to a more assertive posture, breaking with Deng Xiaoping’s advice, which advocated discretion. There has been a clear evolution towards this assertiveness.

In the years preceding Xi Jinping’s ascent to high office, China benignly sought access to raw materials from around the world and low-barrier-entry to export markets. It offered a combination of development aid and infrastructure building in developing countries in exchange for access to local resources, supporting China’s nascent manufacturing sector in the 1980s and 1990s.

As China experienced greater economic success, it continued to invest and finance local and regional projects throughout the 2000s. It was in the 2010s that a more confident China emerged, particularly after Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2013.

The assertiveness initiative is shaping up to overshadow all other objectives that China has.

The 2010s marked the end of a low-profile China and heralded a new era of “imperial ambition” with specific benchmarks set for 2025 and 2050.

The assertiveness initiative was demonstrated by the flurry of China’s diplomatic activity in recent years. A closer look at the flurry of China’s activities allows all its objectives to be classified into three categories: trade (economical), the military and navy (security), and the future battlefield of cyberspace (cybersecurity).

Based on Xi Jinping’s speech during the 19th National Congress in 2017, the year 2050 appears to be the target for ending the co-hegemonic status (i.e., global power sharing with the US). From this goal, one can infer that the intervening years from 2020 to 2050 will be characterized by co-hegemony or a cold/hot war—a period of transition. Setting aside the question of the plausibility of this vision being realized, the mere articulation of this vision lays the groundwork for a prolonged period of active contention between the two great powers. This is our primary argument.

China benefits from US engaging in separate wars to support Israel and Ukraine

The Chinese military principles emphasize avoiding head-on battles against a powerful adversary. Instead, with an element of surprise, they advocate for being proactive and offensive in exploiting enemy vulnerabilities through proxy wars initiated by countries aligned with China.

China maintains strong ties with Russia, which is indirectly engaging the US in the Ukraine war. Similarly, China has deep economic ties with Iran and is estimated to share defence systems. Iran, in turn, financially and militarily supports non-state actors such as Hamas and Hezbollah to engage Israel and the US in conflict.

Moreover, research by the RAND Corporation, a global public policy research organization, suggests that these war theatres are utilized by both the US and China to test their latest military technology, hardware, and operational concepts, potentially preparing for a direct confrontation between the two powers.

Another primary reason for China indirectly engaging its formidable adversary (the US) in an increasing number of proxy wars is to elevate US’ cost of direct conflict to economically prohibitive levels. This cost can also manifest in terms of mounting casualties in proxy wars. The goal is to inflict significant pain on the US solely through these proxy wars. By keeping the US distracted, mired, exhausted, and/or financially drained, the intent is to render it incapable of focusing on containing China’s rise to global hegemon status and its anticipated emergence as a true superpower by 2050.

Prominent Chinese foreign policy analyst like Wang Jisi, dean of the Peking University School of International Studies, has argued that the U.S. war with Iraq benefited China because “It is beneficial for our external environment to have the United States militarily and diplomatically deeply sunk in the Mideast to the extent that it can hardly extricate itself.”

Similarly, Renmin University professor Shi Yinhong has recently argued that “Washington’s deeper involvement in the Middle East is favorable to Beijing, reducing Washington’s ability to place focused attention and pressure on China”.

The rising cost of war shows up in rising bond yields

Even before factoring in the latest costs of the escalating Israeli conflict, the US budget is deeply in deficit. That is, tax revenues are declining due to a weakening economy, the interest bill is soaring due to sharply higher interest rates, and the amount of debt the US government continues to accumulate is staggering.

US Federal Revenue & Spending as % of GDP – living beyond means

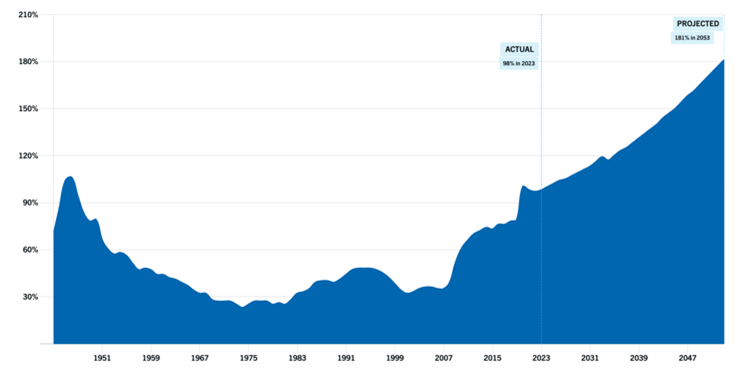

US Total Debt as % of GDP

The US government budget is expected to continue running into deficits, well, forever! Given this outlook, is it any surprise that investors are beginning to question whether they are being adequately compensated for lending to such a spendthrift borrower?

Additionally, the US is likely to pull other allied countries, such as Australia, into similar fiscal deficits due to their anticipated participation in proxy wars and the war-induced global economic recession that now seems increasingly probable in 2024.

Complicating matters, China, which is the focus of the US’s primary power competition, also happens to be its third-largest lender (buyer of US government bonds) after the Federal Reserve and Japan. For the past few years, China has decisively chosen not only to stop lending to the US but also to rapidly reduce its previous holdings of US government bonds. Additionally, Japan is finding it increasingly challenging to lend more to the US due to its own domestic economic issues.

As a result, we now find ourselves in a situation where, at a time of record government borrowing, there is a near-record low number of lenders willing to purchase US bonds. Consequently, bond yields are soaring! If the current situation persists, we could be facing a recession next year. It is thus advisable to maintain a defensive stance in portfolio positioning.

Economic News

In Australia – the central bank (RBA) left the cash rate unchanged at 4.1% in both September and October policy meeting. However, RBA retained a tightening bias with members reiterating further tightening may be needed if prices remain sticky, while acknowledging higher borrowing costs are already beginning to align demand with supply.

In the second quarter of 2023, the economy continued to grow steadily, with the GDP increasing by 2.1% compared to the same period last year and 0.4% compared to the previous quarter. This growth was primarily driven by exports. Despite higher interest rates and rising prices, businesses remained resilient. However, consumer confidence declined significantly in September and reached a “deeply pessimistic” level. Australia achieved its first budget surplus since the global financial crisis in 2008. This surplus amounted to A$22.1 billion over the 12 months ending in June, which is equivalent to 0.9% of the GDP. This surplus was made possible by a very tight job market and high commodity prices, which boosted the country’s financial resources.

In US – The US Federal Reserve decided to keep the benchmark interest rate unchanged. They indicated that interest rates would remain higher for a longer period, with one more 0.25% increase expected this year followed by a 0.50% rate cut in 2024. This is different from the market’s expectation of a 1.00% rate cut.

The Federal Reserve also revised its GDP growth forecasts, raising them by 1.10% for 2023 and 0.40% for 2024. They kept the growth expectations for 2025 and 2026 steady. In terms of core inflation, they lowered their expectations by 0.20% for 2023 but maintained them for 2024 and 2026. They increased the expectations for 2025 by 0.10%.

Consumer confidence declined in September, reaching its lowest point in four months, mainly due to concerns about the economy and the job market. However, short-term inflation expectations dropped to their lowest level since early 2021 in September, with one-year ahead outlook falling by 0.30% to 3.2%, and five-to-ten-year expectations remained steady at 2.8%, the lowest in a year. Factory activity contracted in September, but it was the least contraction seen in nearly a year. This was partly due to strong production growth since July 2022 and an increase in factory employment.

In China – Factories stabilized in September with the official gauge of manufacturing activity returning to expansion in for the first time in 6-months.

In Europe – The European Central Bank (ECB) increased interest rates by 0.25% to 4.5%. However, ECB President Christine Lagarde hinted that this might be the highest point, suggesting a potential shift in their approach. The ECB lowered its forecasts for the euro-area economy, reducing the 2023 GDP outlook by 0.20% to 0.7%, the 2024 outlook by 0.50% to 1%, and the 2025 outlook by 0.10% to 1.5%. They also lowered the core-CPI (Consumer Price Index) forecast for 2024 and 2025 by 0.10% to 2.9% and 2.2%, respectively.

The European Commission also adjusted its estimates, reducing the euro-area’s 2023 and 2024 GDP growth forecasts by 0.30% to 0.8% and 1.3%, respectively. They downgraded the 2023 inflation forecast by 0.20% to 5.6% but increased the 2024 inflation outlook by 0.10% to 2.9%.

In the second quarter of 2023, euro-area GDP growth was revised lower by 0.20% to 0.1% quarter-on-quarter, mainly due to poor export performance. Economic confidence in the euro-area slowed for the fifth consecutive month in September. Consumer confidence dropped significantly, while the services sector slightly declined, and the industrial sector showed some improvement. In September, euro-area Consumer Price Index (CPI) decreased to nearly a two-year low of 4.3% year-on-year, with core inflation slowing to its lowest rate in a year.

In India – In September, the unemployment rate decreased to 7.09%, reaching its lowest point in a year. Joblessness in rural areas dropped to 6.2%, down 91 basis points from the previous month, while urban unemployment also decreased to 8.94%, a drop of 115 basis points. In the same month, manufacturing activity remained robust, surpassing other Asian economies. Both demand and production increased significantly, and businesses gained new customers in important international markets.

In Germany – the economy is expected to shrink in the third quarter of 2023 due to cautious consumer spending, worsening manufacturing conditions, and increased financing costs. Inflation dropped to a two-year low in September, with the Consumer Price Index rising by 4.3% year-on-year. While there was a slight improvement in business outlook in September, it remains historically low, and the economy is likely to contract again in the third quarter. The labour market also weakened, with firms’ willingness to hire employees reaching its lowest point since February 2021 in September.

- Monthly Wrap: US attempting to quell China’s control on semiconductors and AI - July 9, 2024

- April 2024 Monthly Wrap: Economic growth slows to a near 2-year low as inflation growth delays interest rate cuts - May 10, 2024

- Monthly Economic Wrap: Rate cuts, a Chinese nuclear arsenal and impending TikTok ban - April 5, 2024

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.